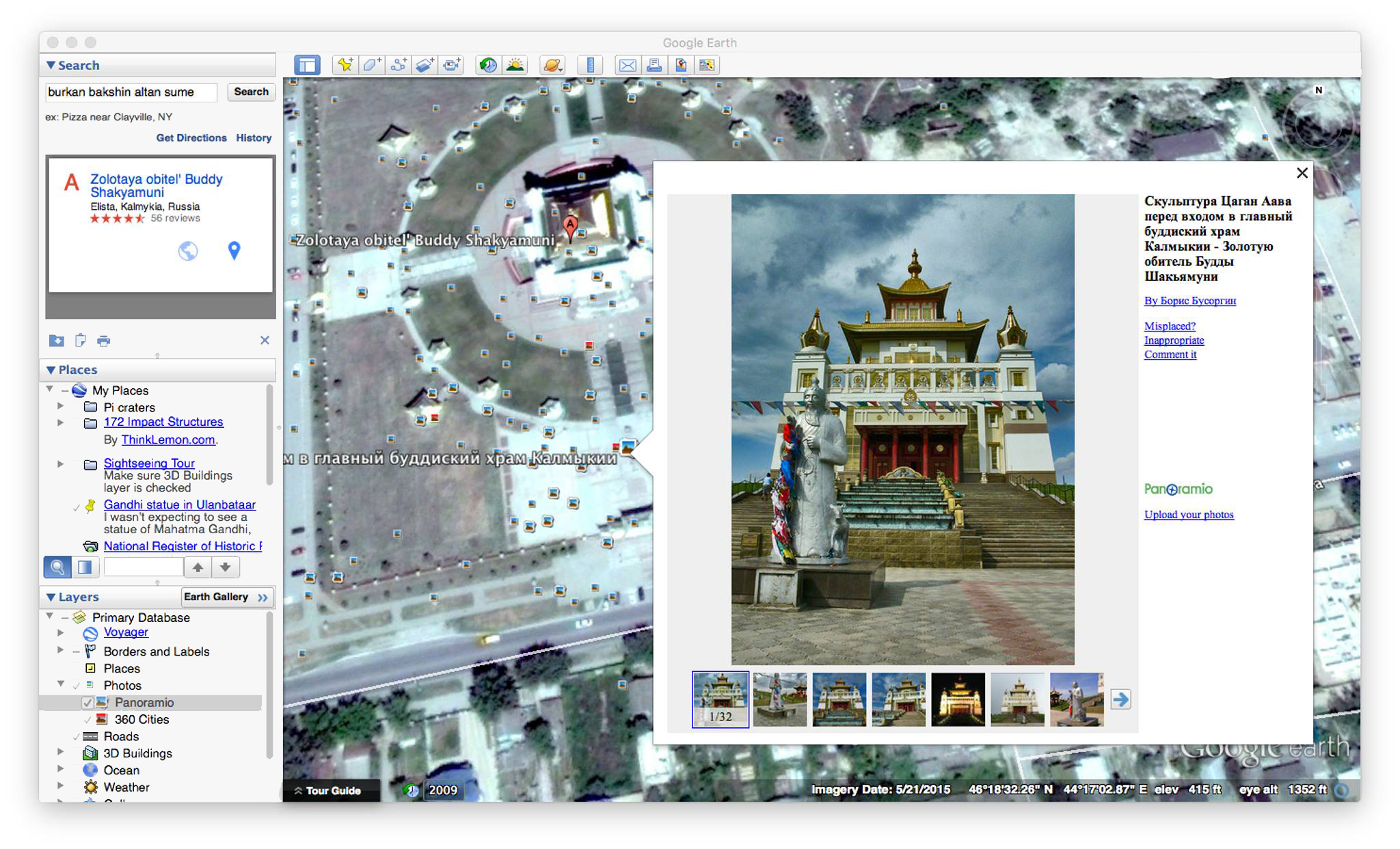

If there’s one thing I am obsessed with – other than democratizing science, learning from data, evidence-based practice, people who aren’t what they seem, exploring the world with Google Earth, and Australian Rules Football – it’s flags.

If there’s one thing I am obsessed with – other than democratizing science, learning from data, evidence-based practice, people who aren’t what they seem, exploring the world with Google Earth, and Australian Rules Football – it’s flags.

A flag is a symbol of a group of people, a source of pride, and looks beautiful waving in the breeze. A flag represents all the best and worst impulses of humanity. When they all come together, like at the United Nations, you get a real sense of how we all come together as a world.

I’m not alone; there is a large and somewhat nerdy community of flag lovers called vexillophiles, from the Latin for “lover of flags.” We have an unofficial website, multiple YouTube channels, and an international organization (which of course has its own flag.

In my interactions with fellow vexillophiles, I have discovered an informal, tongue-in-cheek personality test, which is:

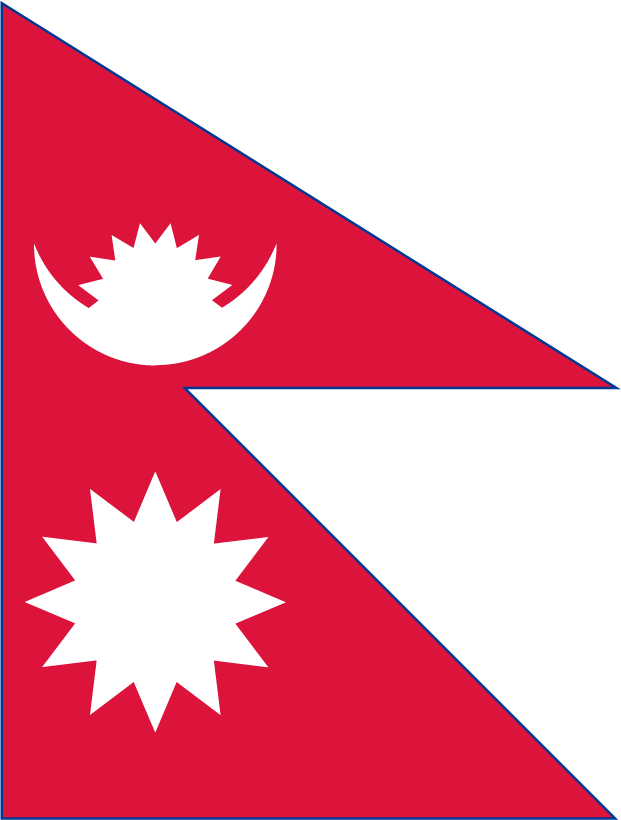

What do you think of the flag of Nepal? Is it kind of cool, or is it an Abomination Unto Flags?

The flag of Nepal, shown in the photo above and the illustration here, is the world’s only non-rectangular national flag (although there are some sub-national nonrectangular flags, most famously the state of Ohio and the city of Tampa, Florida). It consists of two red triangles, the bottom one slightly larger. The top triangle has a stylized, symbolic drawing of the moon, and the bottom has a similar drawing of the Sun. Both triangles are outlined with a thin blue border.

To be in the first category, you don’t have to like the flag, it’s enough to say, “that’s kind of cool, I respect what they were going for there.” Being in the second category requires strong opinions about what does or does not constitute a “real” flag.

Your opinion on the Nepal flag correlates with many other things, especially your opinion about whether people should get off your lawn. It’s not an absolute predictor, and of course correlation is not causation, but it’s an effect that I have noticed.

Zero guesses which side is the “get off my lawn” side, and zero guesses which side I’m on.

(Spoiler alert, highlight to reveal: It’s cool.)

Nepal flag photo: Hom Lamsal, Nepal Republic Media

Nepal flag illustration: Wikimedia users Pumbaa80 and Achim1999.