EDIT: I originally said Oregon’s 5th district was still undecided; it was actually Oregon’s 6th district, containing the far southwestern suburbs of Portland

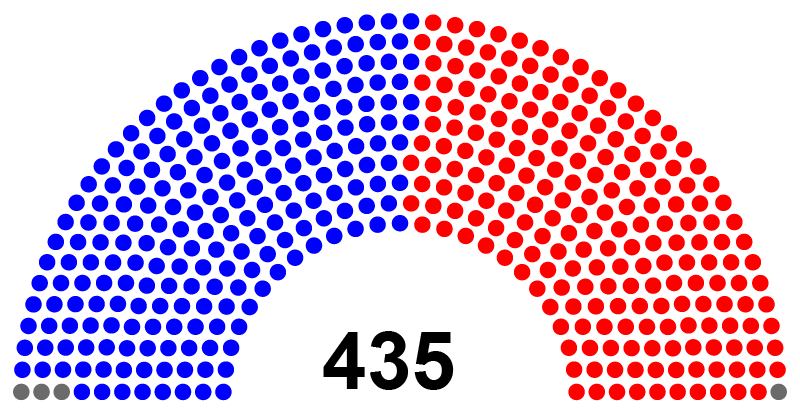

We still don’t know all the members of the House of Representatives for the incoming 118th United States Congress. We don’t even know which party will be in the majority.

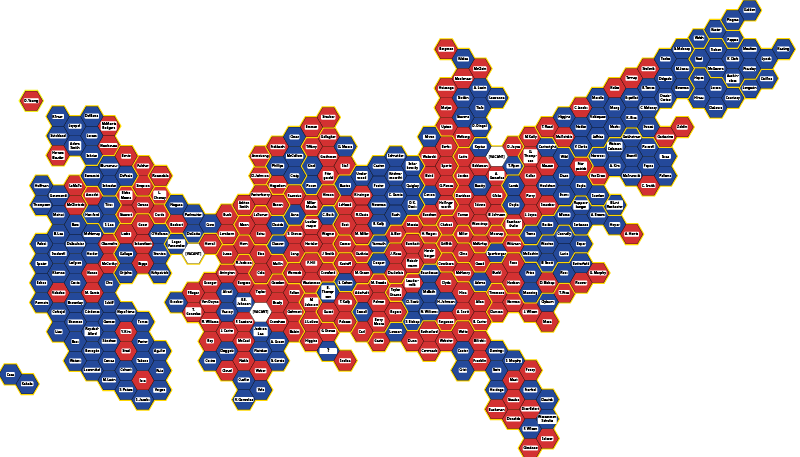

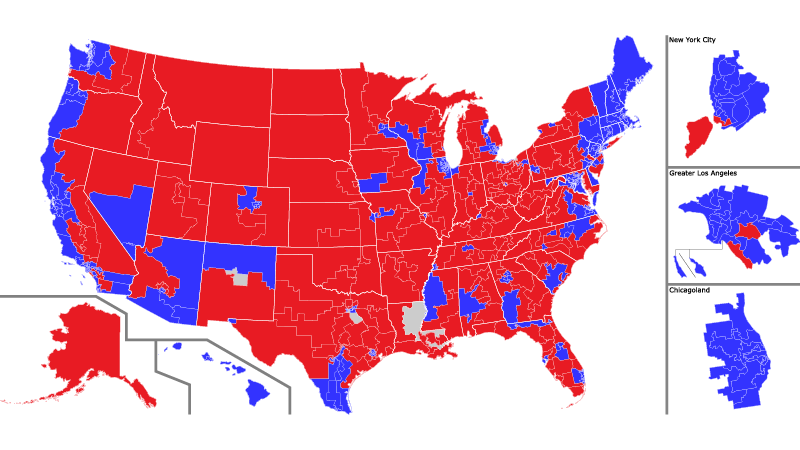

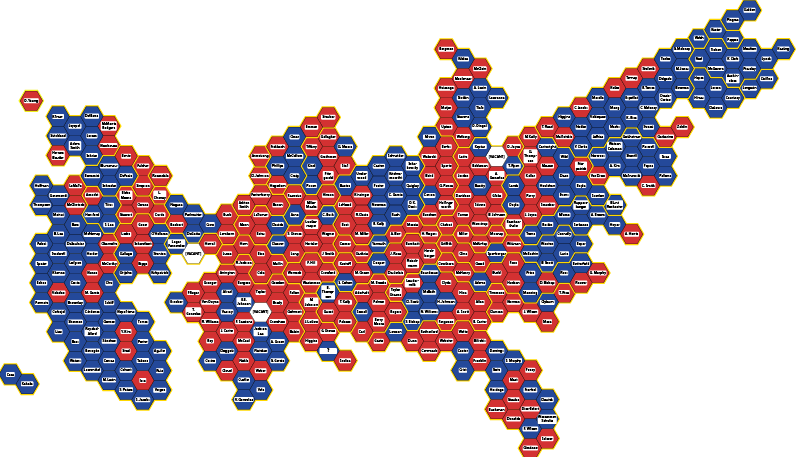

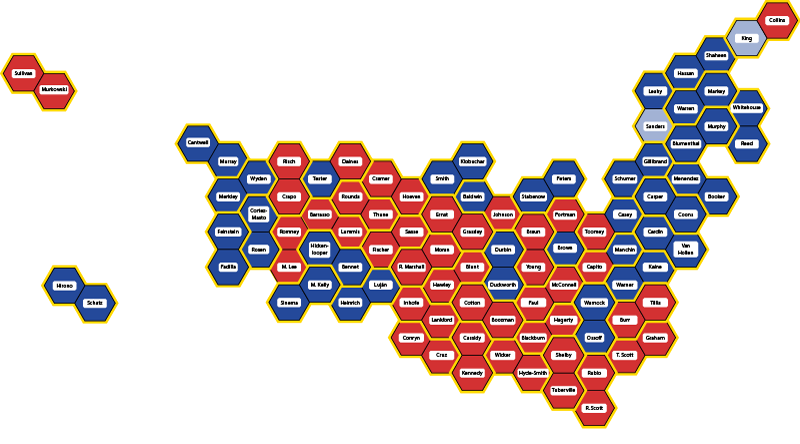

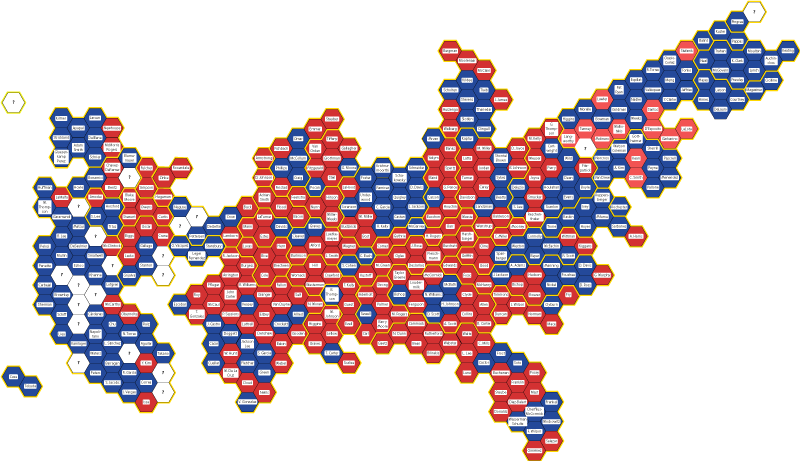

Here’s what we do know so far, presented in the usual Mapping Democracy map style. White ? hexagons are seats that are still undecided. Click for a larger view.

Red = Republican

Blue = Democratic

White = party undecided

Click for a full-size version.

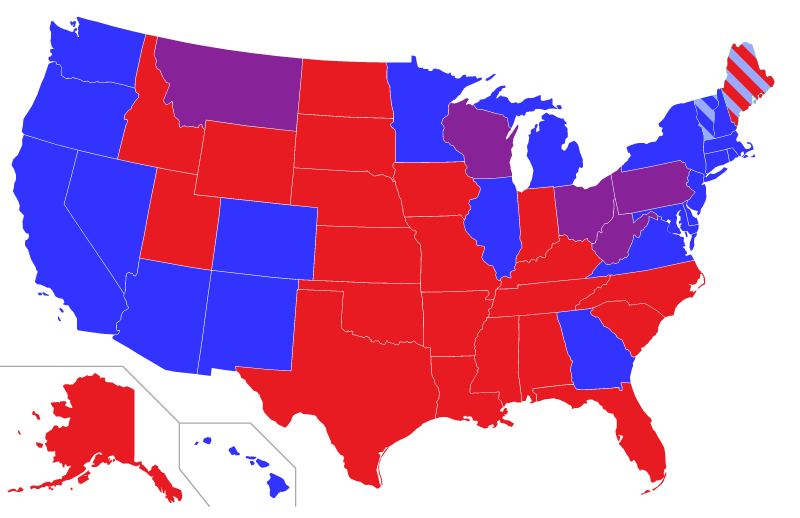

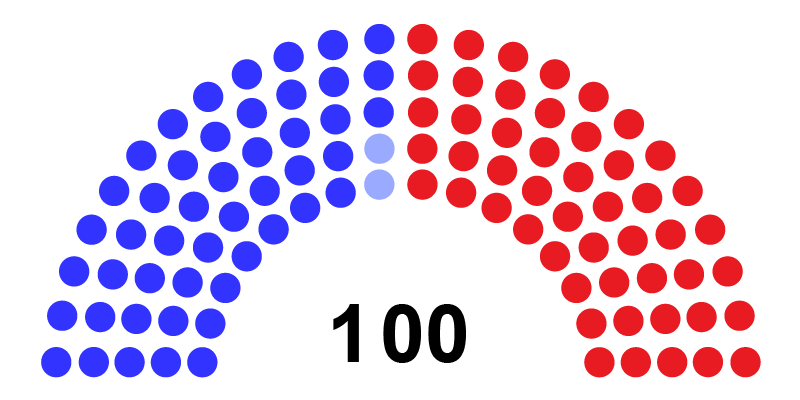

The current count by party is Republican 212, Democratic 203. Twenty seats are still up for grabs: one each in Alaska, Maine, New York, and Oregon; two each in Arizona and Colorado; and twelve in California. Halfway, at 218 seats, is enough for control – so Republicans must win six of the remaining seats to hold the advantage. That seems likely, but whothehellknows.

If Republicans do get the majority, what happens? Obviously, it would be harder to pass legislation with different parties controlling the House and Senate – but maybe not impossible. Remember that Republicans in the House will face the same Joe Manchin Effect a the Democratic Senate – the closer the margin, the more people will need to be convinced to vote for the party line. And representatives from competitive districts will have an incentive to show their voters that they are willing to stand up to the party line.

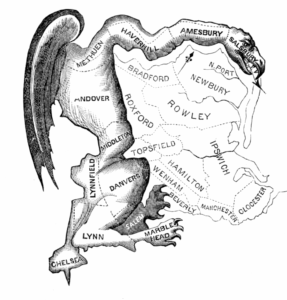

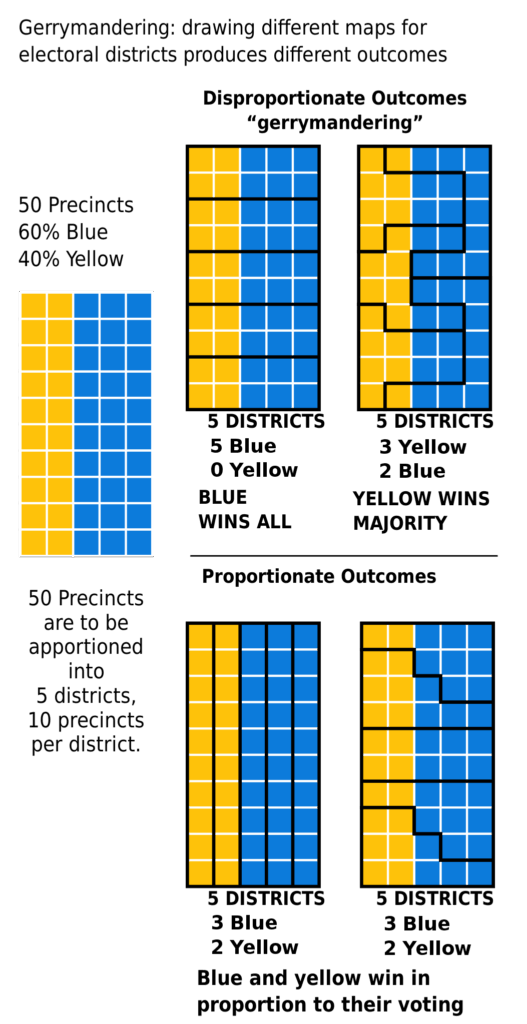

With gerrymandering, are there enough competitive seats to make a difference? Yes, obviously – after all, there are still 20 seats up for grabs now, nearly a week after votes were cast. Here are those districts, with information about where they are:

Alaska at large: the entire state

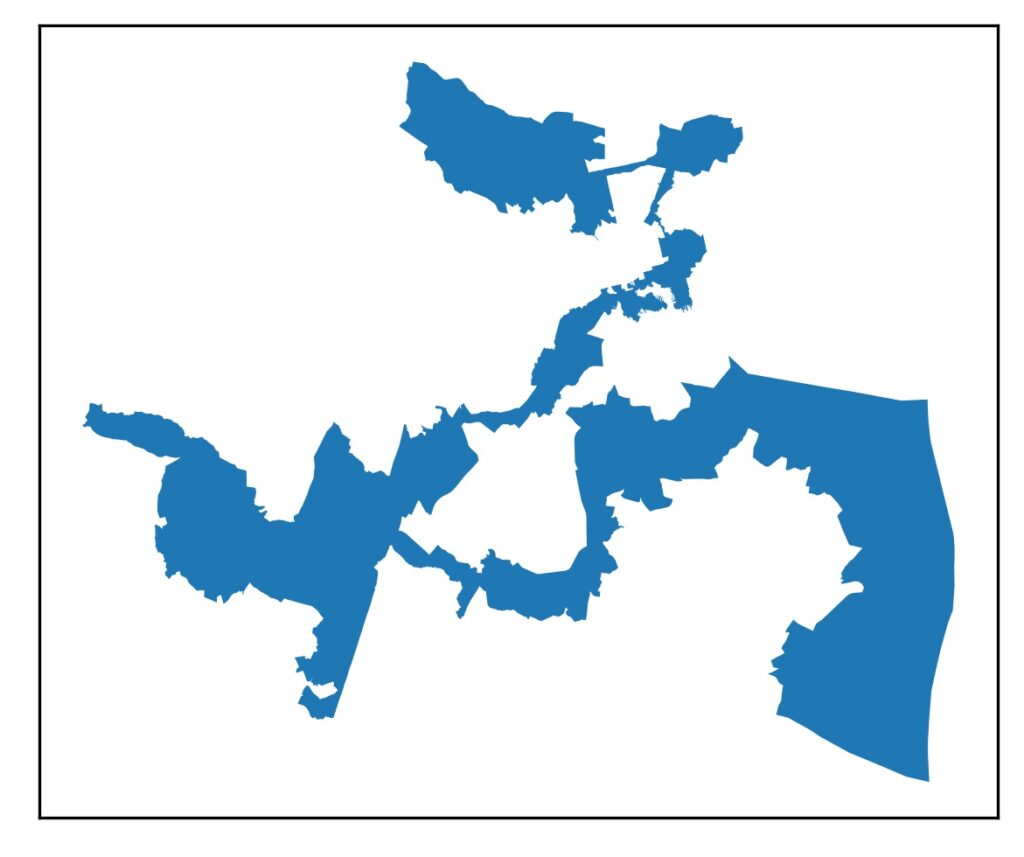

Arizona-1: the northeastern quarter of the state, plus a gerrymandered bit of the northwestern suburbs of Phoenix – parts of Scottsdale and Paradise Valley

Arizona-6: the northeastern suburbs of Phoenix, including parts of Scottsdale and Paradise Valley

California-3: the rural Sierra Nevada mountains and the northeastern suburbs of Sacramento, including Roseville

California-6: the northern half of the city of Sacramento, and parts of Arden-Arcade and Rancho Cordova

California-9: Stockton and surrounding areas of San Joaquin County

California-13: Merced and surrounding areas

California-21: Fresno and the southern San Joaquin Valley

California-22: The eastern half of Bakersfield and rural areas to the north

California-27: Northern Los Angeles County, including Lancaster, Palmdale, Glendora, and Pasadena

California-34: The eastern part of the city of Los Angeles

California-41: Moreno Valley, Palm Springs, and the southern part of the city of Riverside

California-45: Irvine and northern Orange County

California-47: Long Beach and coastal Orange County

California-49: Oceanside and San Juan Capistrano

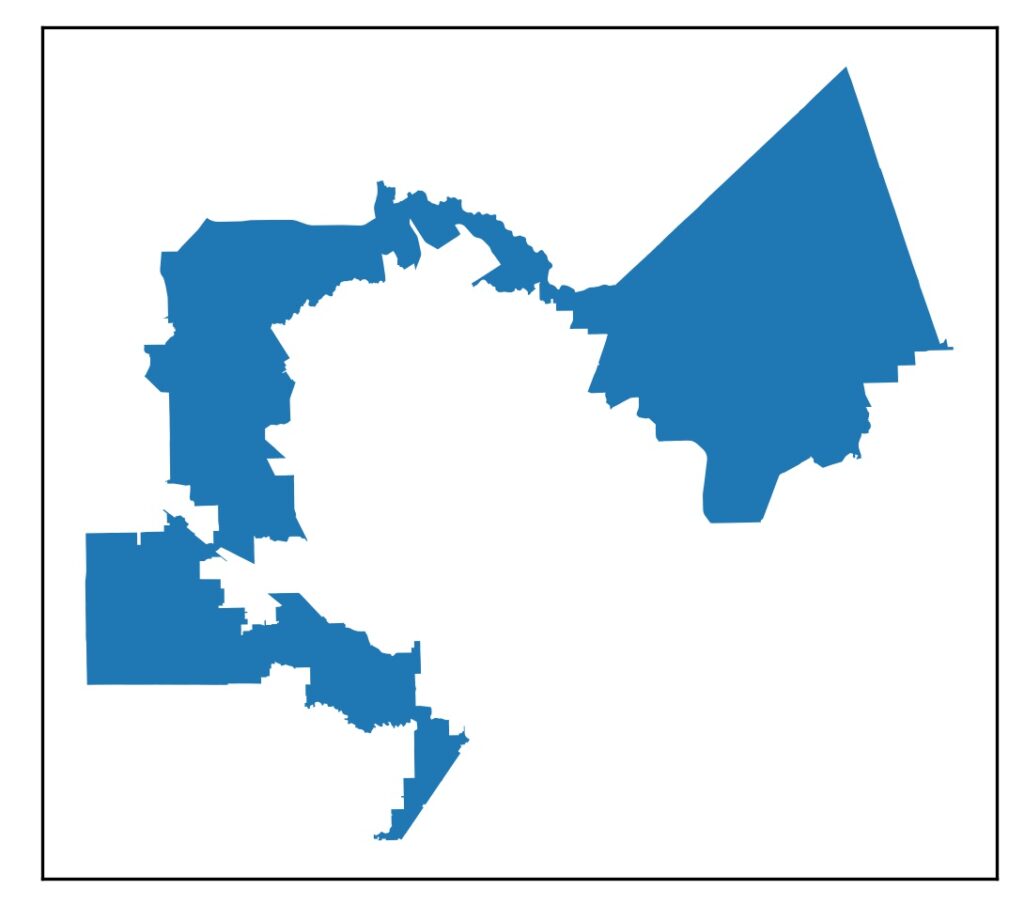

Colorado-3: Pueblo, Grand Junction, and the rural western third of the state

Colorado-8: Northeast of Denver

Maine-2: Mostly-rural northern and eastern Maine

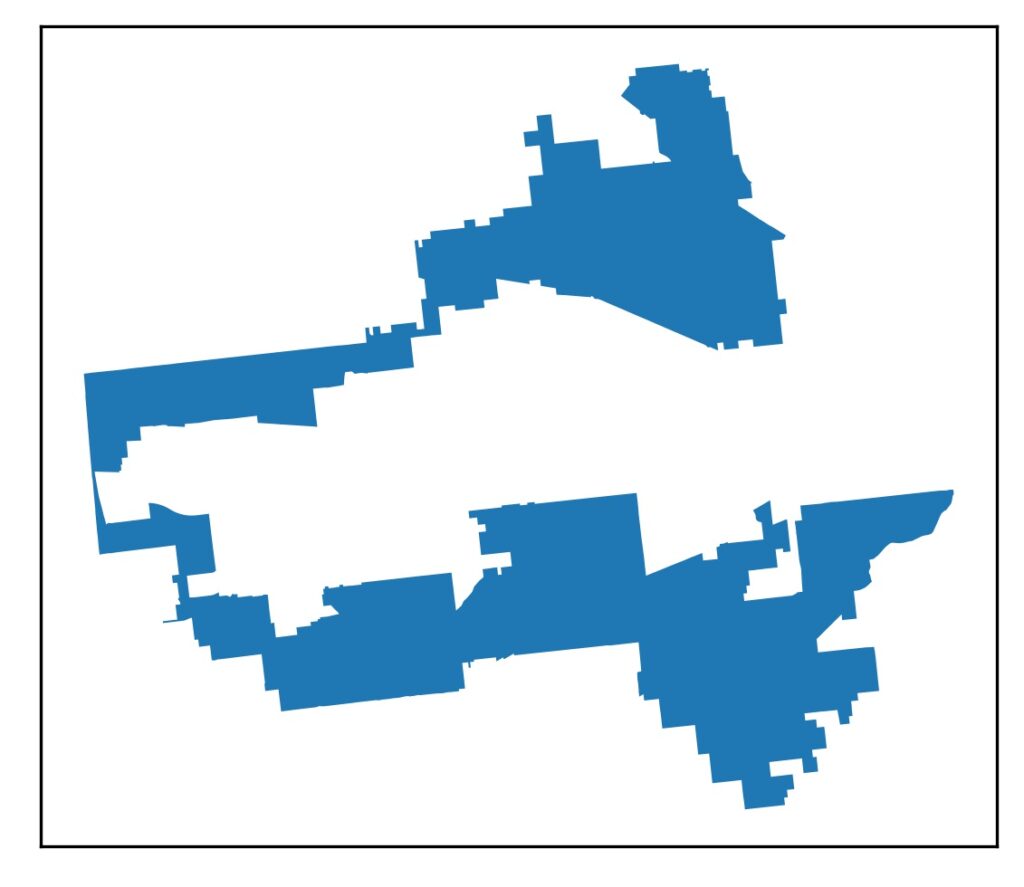

New York-22: Utica, Binghamton, and surrounding areas

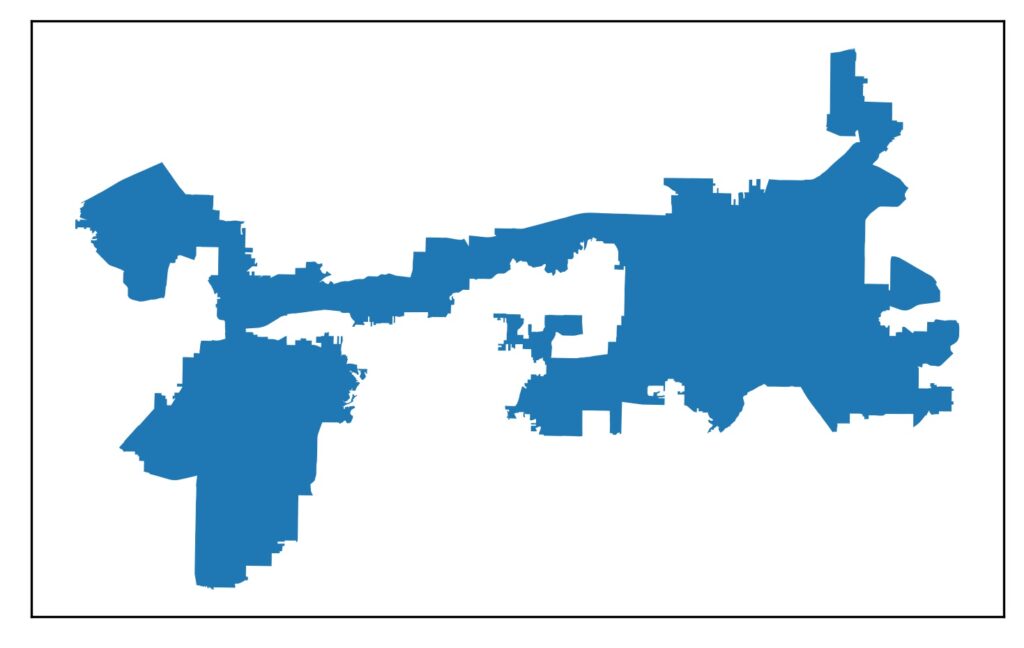

Oregon-6: The southwestern suburbs of Portland

As results are announced in these 20 districts, I’ll update the non-misleading map accordingly.